Wouldn’t it be great if we had a step-by-step recipe when it came to building the ultimate tennis champ? Just add 10 years of skill training, a half-decade of physical development and a sprinkle of mental skills...and voila, a world-class player, just like that!

Jokes aside, the topic of ‘what it takes to get to the top’, is eternally interesting. Whether you’re a coach, parent or athlete, achieving high levels of success in your chosen sport, is often a lifelong dream. The odds, however, are stacked against us all.

But why is that? Why do some achieve greatness while others are left in the dust? You’re not the only one asking these questions. Researchers want to gain more insight into this puzzle as well - now more than ever.

In particular, two researchers - Dave Collins and Aine MacNamara - have been exploring this topic for a number of years. Their work may help us attempt to solve this eternal puzzle - what separates the very best from the rest?

Their research classifies athletes into one of 3 types...

Super Champions (SC): athletes who won multiple international championships at the highest levels.

Champions (C): competed at the highest level, but did not have the same pedigree of success as SC.

Almost Champions (AC): achieved well at the youth level but only competed at the second tier professionally.

Ultimately, we want to know what typifies the attitudes and behaviors of high achievers, compared to their second-tier counterparts? Is there something we can learn and adopt from the very best? Is life or sport adversity - as the research suggests - a pivotal factor in the success, or failure, of an athlete?

In revealing the findings, we’ll look at how each class of athlete responds to setbacks, how a support team ‘should’ act and the characteristics necessary to forge the ‘Super Champ’.

The Mindset of a High Achiever

According to Collins et al (2017), the biggest factor that separates SC from C and AC is a ‘learn from it’ attitude. There’s no argument that all athletes, at some point in their careers, experience adversity. Fundamentally, it’s an athlete’s response that enables one to flourish while another to perish.

Take for example, what one Almost Champ recalled of a serious injury:

“I sort of lost enthusiasm for it because…I almost felt let down, especially before the second operation… why was my injury different from anyone else’s, how come mine had to be 14 months for the same surgery that someone else had done for 3 months?”

Even Champs - those who competed at the highest level of their sport - echoed similar sentiments, playing the ‘blame game’ for their lack of progress:

“Well the sort of 10 to sort of 17, 18 years should be a natural yearly progression. But because I broke my arm, I didn’t improve, I just sort of stood still for 18 months. And it was an issue because when my arm got fixed I hadn’t grown, and everyone else seemed to have grown.”

Super Champs had a completely different outlook when it came to a traumatic setback. While they also felt the disappointment, the frustration...instead of blaming and projecting towards external factors, they framed the incident as an opportunity for growth:

“That injury was pretty crucial I think. . .I was going well before it but the disappointment. . .the pain. . .it just kicked me where it hurt and I was determined to get back.”

Another SC had this to say about the injury that set him back:

“No never, never ever thought about giving up. There were days when I was like ‘Why is this happening to me? I’m so frustrated, what am I going to do? How long is it going to take me to get back?’ But then the other days were like, ‘right what do I need to do? I’m going to do this, do this and get back’....I think that gave me a different mental capacity. Because I’d never had to deal with anything like it before....it changed me and made me achieve what I then went on to achieve.”

Given these powerful reactions from high achievers, you get the sense that they use setbacks as motivation, a driving force that catapults them to not only get back to where they were before, but to learn from the experience and to be better than ever.

What facilitates this ‘learn from it’ attitude? Can it be developed?

While the research suggests that high achievers may have better inherent coping habits (Collins et al 2016) the stronger argument seems to be that SC either don’t acknowledge the setback the same way as low achievers do OR they don’t even perceive the ‘trauma as traumatic as others do.’

On the flip side, this self-defeating attitude, most commonly typified by the behaviors of low achievers, inhibits growth. For instance, instead of putting things into perspective and finding solutions after a setback, they do the opposite:

“rather than staying at training and thinking ‘right I’m going to work hard, I’m going to really focus on my crossing, or really focus on that,’ I did no extra work. I didn’t go to the gym, I didn’t eat the best foods.”.

High achievers, on the other hand, see the same challenge in a completely different light:

“Not making that selection, especially after all that work. Several others just said f*#! it, but I was never ever going to let them beat me. I just did double everything!”.

And beyond the setbacks, even when things go well, Super Champs strive for more:

“I was never kind of satisfied, I was never like ‘Oh I’ve done it now’ I was always like ‘This is the first step of my journey’”.

Some of these negative responses to setbacks, according to researchers, are a result of Talent Development (TD) pathways. These centers for excellence are actually ‘smoothing’ the road for young up-and-coming athletes, they argue. The adversity necessary for growth, from their point of view, isn’t seen until later in a TD athletes’ career, when it’s perhaps too late. To resolve this, they propose that ‘structured traumas’ be strategically implemented into the programs of emerging sports stars.

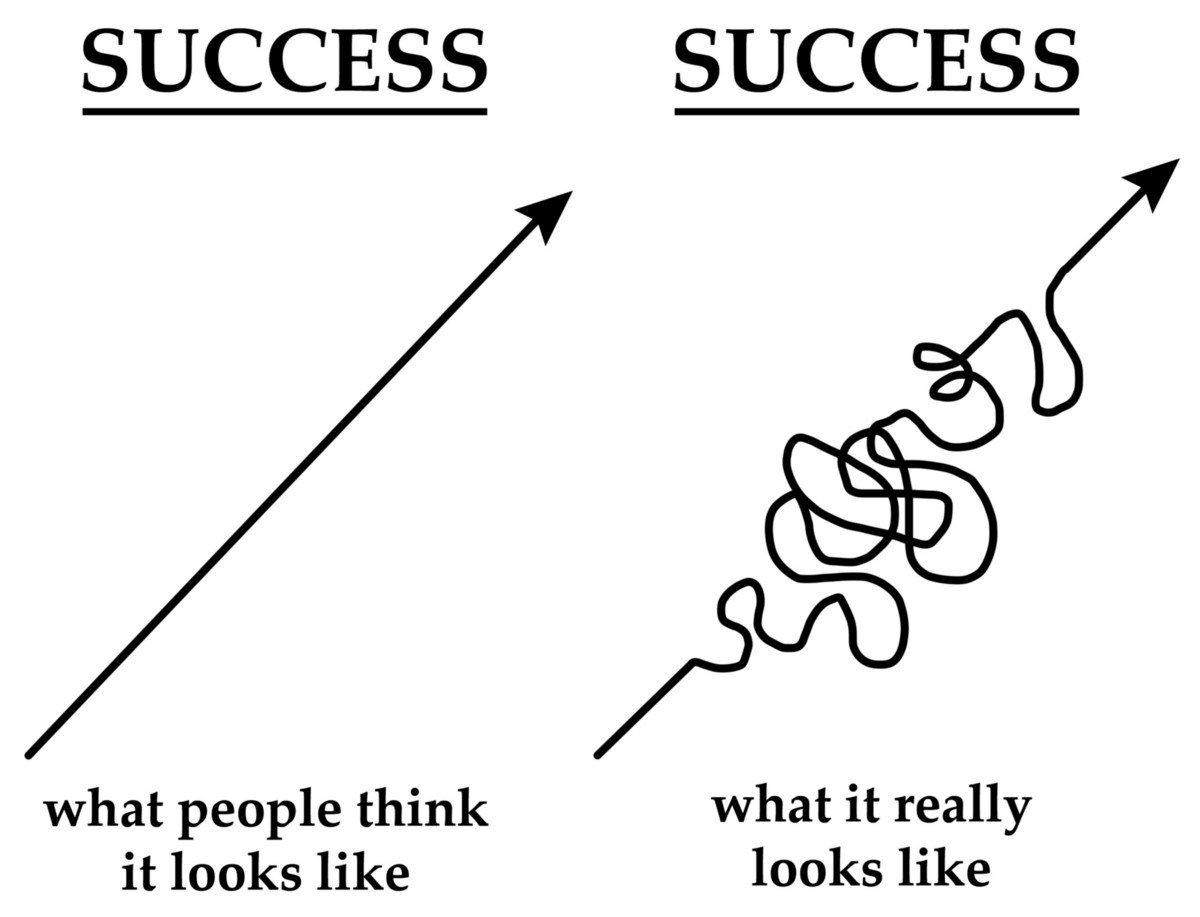

These ‘manufactured traumas’, according to Collins, could include training with a new group, being de-selected from a camp or even a temporary increase in training load. But is this the answer? Whether it is or not is still up for debate - but one thing’s for sure, the path to the top is anything but linear.

Sure, many young athletes excel and progress rapidly early on. As they get older, however, and begin competing with others of similar class, that progress can feel like a sudden halt - at times, it can even mean a step or two back (not something youth super-athletes are accustomed to).

How many Roger Federers and Serena Williams’ are there? Not many. Some of the greatest tennis players of all-time had to overcome injuries, adversity, naysayers and their own internal demons. Look at Agassi. There was a stretch of time where he was lost, dropped outside of the top 100. Many thought his career was over. But he persevered. Eventually, he reached number 1 in the world and is now regarded as one of the greatest champions of all-time.

So it’s not that the AC can’t make it, it’s that they lack certain mental traits and skills to stay the course, especially in the face of adversity. The elite class, when hit with a setback, seem to believe their best is yet to come (Savage et al 2017). Now that’s powerful.

Quiet Leaders - The Role of Coaches and Parents

It’s not always the athlete’s fault. Research seems to indicate that there’s both a nature and nurture element to coping with adversity. Some athletes are born with positive personality traits like optimism, hardiness and resilience. But that doesn’t mean that these attributes can’t be developed. So instead of throwing in the towel, support staff should frame these ‘tough’ moments as opportunities for skill building and character growth.

According to Collins, a big difference does exist between the involvement of coaches and parents of high-achievers, versus those mid to low-achievers. Interestingly, SC recalled their parents being supportive but not very closely involved in the process. They’d encourage their children to pursue their goals - drive them to and from practices, attend games and cheer from a distance - but they would leave the nitty gritty details to coaches. Here’s one account from a SC:

“[my parents were] not really pushy, it was kind of just gentle encouragement. They were never really involved, they’d just come and watch me, support me. But they never wanted to know what I was doing training wise and they never really got involved in that way, and that helped.”

ACs, on the other hand, were constantly being pushed by parents and coaches. To the point where one athlete actually felt as if the joys of sport were taken from them:

“My parents, dad especially was always there. . .shouting instructions from the touchline, pushing me to practice at home. Really, I just wanted to be out with my mates, even though we would still be kicking a ball around. I felt like [sport] stole my childhood.”

A few years ago, as part of the coaching team for Britain’s next female tennis hope, I encountered a similar experience - a father who attended every session, not as a casual observer, but as a vocal distraction. He’d shout at his daughter’s so-called ‘lack of effort’, grimace when she missed a forehand...and not once did he have a kind word to say. The result - at 15 years old, this rising star left the game and never returned.

This isn’t just a one off example, this happens all too often in youth sport today - parents obsessing over their children’s every sporting move.

What about coaches?

When it comes to coaches, there was a clear dichotomy between the experiences of Super Champs, and Champs/Almost Champs. These mid to low achievers seemed to work with coaches who were either always in their face or looking for a way to ‘ride the athlete to the top.’

One athlete stating - coach was ‘always wanting to dissect my performance...He was very intense and, as I got older, it really started to antagonize me.” An Almost Champ had a similar recollection:

“X was the driving force. When I was younger, he would collect me from home, drive me to the club, train me then drive me back. . .talking about [sport] all the way. Let me tell you, it was f∗∗∗∗∗ intense.”

Contrast these experiences to that of Super Champs:

“I think [coach's name] was great in the fact that he never wanted to rush anything whereas I always did. I wanted to be better, and I wanted to start winning things straight away. He always had in his mind that it was a long journey. And that’s the sort of thing that worked so well, he developed me as an athlete really slowly so I would always achieve the things I wanted to achieve later on in my career.”

Many successful coaches across a variety of sports realize the commitment involved at the top. They understand that athletes are devoting their lives to sport. The constant over-analysis of practices & games can at times be too much. It’s another form of stress. Mike Babcock, pro hockey coach, aims to talk about more than just hockey with his players. That’s not to say there isn’t a time and place to ‘dissect’ a performance, but when it’s constant, that’s when it can be detrimental.

Perhaps a better option, one that ALL elite coaches use, is to simply engage in regular debriefs. After a practice, a game or a season, it’s absolutely vital that athletes sit down with a member of their support team for a review. These debriefs, according to elite coaches and researchers, can at times be more impactful than practices - the key is to know your athlete and when the right time to talk is (it can happen directly after a practice/game or several days afterwards...each athlete is different). I’ve found that immediately after a loss is the worst time to talk to most players.

But it is a time where full transparency and honesty are at the forefront. Didn’t have the right mindset at practice, the athlete has to know. Focus and concentration on relevant tasks were absent, that’s a talking point. The truth has to come out. The important thing to remember here is:

Critique the behavior, NOT the individual.

Overall, it’s a facilitative approach, rather than a directive one, that seems to contribute to that ‘learn from it’ attitude seen in high achievers. Low achievers, having too much info thrown their way, have a poor time coping with adversity. Coaches and parents can adapt their involvement to fit the needs of each individual athlete.

The ‘Unique’ Traits of ‘Super Champs’

These findings are taken from only a handful of studies - and less than 100 athlete responses. There’s still a lot we can learn - but some of the early findings are promising. For one, we know that high achievers internalize setbacks and go through a reflective process - this ultimately drives their behaviors in a positive manner. Low achievers, on the other hand, seem entirely ‘reactive’. As we noted above, this contrast is likely a combination of the ‘learn from it’ approach to challenge along with an encouraging (but not overbearing) support structure.

Furthermore, the main differences between the best and the rest, according to Collins, were the psycho-behavioral characteristics of Super Champs - including commitment, coping with pressure, self-awareness, goal setting, effective imagery and more.

Researchers once thought these characteristics were solely developed after a traumatic event - the literature terming this ‘post-traumatic growth theory’. The premise being that athletes need regular opportunities to deal with traumatic events and that these events in themselves, build the necessary mental skills & behaviors, over time. In other words, ‘talent is caused by trauma.’

Recently, however, autobiographies from several Olympic swimming champions (Howells and Fletcher 2015) found that they didn’t have to learn anything new when coping with a trauma, rather, they used skills that were already established. This is supported by other Olympian medalists (Sarkar et al 2015) with authors concluding that “performers should be given regular opportunities to handle appropriate and progressively demanding stressors, be encouraged to engage with these challenges and use debriefs to aid reflection and learning.”

The take-home: athletes need to possess some of these skills and traits before being encountered with a trauma or setback. As Savage et al 2017 exclaim, talent isn’t caused by trauma per se, ‘talent needs trauma.’

Inevitably, what this tells us is that coaches should be constantly seeking to improve all facets of an athlete’s game - including aspects that aren’t necessarily as noticeable as a player’s forehand mechanics or 10m sprint times. But how often do we take a portion of a training session to improve imagery skills? Or to improve one’s self-awareness? Overall, mental toughness isn’t a result of suicide drills and grinding training sessions. As coaches, we must plan the development of these skills just as meticulously as we would a block of speed & agility training.

Lastly, from a research perspective, we’re only scraping the surface of what we know about ‘super champion’ performers. A lot of the same can be true in practical settings - even elite coaches aren’t always sure why a certain athlete had great success, while another didn’t. This, however, is a starting point - if we have an idea as to which behaviors are championing vs those which are defeating, we can devise a proactive plan to facilitate the growth of the latter. For the moment, it’s up to coaches to facilitate rather than direct, the athlete’s growth - mental, physical or otherwise - and treat the training process as a playground for learning.

Once you’ve read the article, I’d like to hear from you:

What are the most important characteristics of a Super Champion? Name 3 in the comments below.

WANT TO BE UP-TO-DATE ON THE LATEST SPORT SCIENCE AND TENNIS RESEARCH?

No spam or fluff - just the most comprehensive articles on tennis.