Many of you have probably heard of the acronym SAQ. If not, it’s referred to as speed, agility & quickness. Coaches & trainers from a variety of sports use these terms liberally and interchangeably. This is a problem. In the tennis world, many believe that these 3 qualities are supremely important for the movement success of an elite player. Another problem. When it comes to speed, are we referring to maximum speed? Or something else? In tennis, as we’ll see later in this post, a player almost NEVER reaches top running speeds. Is it relevant then? Quickness, on the other hand, has multiple issues. First, what does it even mean? Does it mean being explosive? Does it deal with having fast feet (which is a misleading term in itself). Prominent researchers disregard quickness as a sport science term anyway; their reasoning...it’s too vague.

That leaves us with agility. Agility is in fact a VERY important quality every tennis player must possess. But it’s also a term loosely used in tennis training circles around the world. You may think that a simple spider drill (video below) is an agility drill. If so, you’d be wrong. In this post, I’ll attempt to differentiate between agility and it’s little brother, change-of-direction (COD). One of them is highly dependant on the other. We’ll define both terms, link tennis to each of them and provide a mechanical rationale to develop the latter quality, COD.

Change-of-Direction vs Agility: Definitions

Agility and COD ability have been used interchangeably but they are NOT one and the same thing. It’s important to define both terms as this will strongly influence our view of each as they relate to tennis. It'll also help guide the organization of training in very specific ways. Let’s start with agility. Young et al (2006) propose this definition:

"A rapid whole-body movement with change of velocity or direction IN RESPONSE TO a stimulus. This definition respects the cognitive components of visual scanning and decision making that contribute to agility performance in sport."

There are 2 key factors in this definition. First, that changing direction in the context of agility is predicated on the presence of a stimulus and second, based on this stimulus, there's a decision that needs to be made. In tennis, this is pretty evident. Every time a player makes a movement towards the oncoming ball, they have perceived the ball, made a decision and only then can they execute a movement. Let's compare this to the definition of COD ability, “a rapid whole-body movement with change of velocity or direction that is PRE-PLANNED”. See the difference? The former involves a perceptual decision, while the latter does not.

A Closer Look at Agility in Tennis

Here are a couple examples. Returning serve would be classified as an agility task. A player must make a perceptual decision based on relevant cues - the server's stance, ball toss, arm action, racquet path etc. While when recovering after your serve, you'd likely think of this movement as pre-planned. If that were the case, wouldn't we classify the recovery in tennis as a COD task only? In other words, there's no stimulus, just get back to your recovery spot as fast as you can, right? This may or may not be true. Will your recovery be influenced by where your shot lands on the other side of the net? Or by the positioning of your opponent? At an elite level, I think so. Whether recovering in tennis is an agility OR COD task is still up for debate. But I don't think it really matters. What matters is that you know the difference between the 2 terms and the fact that COD's part is STILL relevant. Look at figure 1 below. Although COD is NOT agility, agility does require COD. And COD has many sub-components that play a big role in its successful execution.

Figure 1. Universal Agility Components

At an elite level, anticipation skills will be quite high for most players (I mean they wouldn’t get to that level without them). Good anticipatory skills will help you react faster to the oncoming shot, but you still have to move to the right spot, and that requires superior physical qualities - ones that will enhance movement skills. This is why training COD irrespective of agility, is still important.

In another post, we'll explore the perceptual side of agility in more detail. Sign up for the Mattspoint newsletter so you won't miss out!

Another Look at Movement in Tennis

I’ve spoken on many occasions about the modern game of tennis - check out this article on the WTCA site for a more detailed look. Recall that tennis is characterized by short rallies, short distances and low movement velocities. Don’t believe me? A recent study (Pereira et al 2017) took a closer look at these parameters in professional (ATP Futures level) players. Here are some interesting results from the study. First, rally lengths were just over 4 seconds long, on average. The total distance covered per rally was about 5.5m. Another interesting finding was the differences between lateral and forward displacements - lateral movement occurred more than 75% of the time AND when moving to the side, the distances were much shorter (unfortunately, no backward displacements were mentioned). Lastly, and perhaps most intriguing for me was the movement velocities. An astonishing 79% of the time, players were moving between 0 and 7 km/h!! Another 17% of the time was spent between 7-12 km/h, 3% between 12.01-18 km/h and a measly 0.3% between 18.01-24 km/h. How are you training for tennis? Remember, from a previous post (Strength for Tennis), when velocities are low (around 0-7 km/h), forces have to be high, otherwise it’ll be a challenge to produce movement. And to exert a lot of force, we need to have exceptional leg strength, as we’ll see next.

Change-of-Direction & Tennis - Physical Factors

I attended a presentation a couple years back at a tennis federation - the topic was COD ability. The presenter was refuting strength training as a key component to this COD ability. The argument was that coordination is the key. Don’t get me wrong, coordination is important, but it’s only 1 aspect. Look at the figure above again. Young et al are some of the leading researchers in sport science on this topic. They don’t disregard coordination (technique as they put it) but they have observed through research and experience that other factors MUST be considered. Interestingly, the arguments of the presentation were based on a review paper that was published in 2006. Since then, there have been several studies that have reported strong and significant correlations between strength training and COD ability.

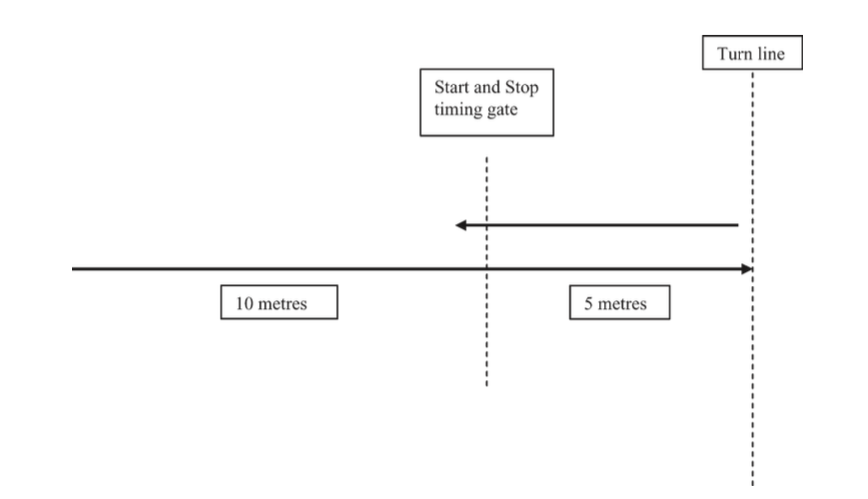

Furthermore, as we saw from Pereira et al (2017), the distances covered are very short in tennis. Most studies on strength training and COD have analyzed longer distances (10m shuttle, Illinois test etc.). These are in no way specific to the demands of our sport. Probably the best measure of COD ability in tennis is the 505 test (figure 2) because the distances are more reflective of what you'd see on court. And as I've mentioned previously, short distances have huge acceleration and deceleration demands, which require high force outputs...and strong, powerful legs. Based on this knowledge and the sub-components of COD presented by Young et al (2002), I’d like to focus on anthropometry & leg muscle qualities - and their relationship to COD movement abilities.

Figure 2. 505 Test - Subject begins at the far left)

Leg Muscle Qualities

Let's look at 2 of the qualities presented by Young et al (2006) in more detail. Reactive strength (I’ve spoken a couple times about the importance of reactive strength in tennis, highlighting it’s prevalence during the split-step) and concentric strength & power.

Concentric Strength

Concentric (muscle shortening phase) strength & power is the propulsive phase of COD. In other words, after you’ve decelerated & hit your shot, you must re-accelerate towards your recovery position - this re-acceleration is your propulsive phase. To re-state, re-acceleration/first step ability requires both maximum and explosive strength abilities. The more force you can generate into the ground AND the faster you can generate that force, the more effective your propulsive ability will be, getting you back into a better ready position for the next shot. A 2015 study (Spiteri et al) on female basketball players showed a significant and strong correlation between propulsive force - the amount of force (N) - from 0 velocity to initiation of movement - relative to body weight (kg) AND exit velocity (along with subsequent 505 test times). What this means is that generating a high amount of force relative to body mass, will essentially improve COD ability. Simply put, increase concentric leg strength and you'll see improvements in first step ability - whether that's moving to the ball or recovering after you've hit.

What Young left out however, was the 2 other types of muscle contractions, eccentric (muscle lengthening phase) and isometric (no change in muscle length but force produced nonetheless). Both are EXTREMELY important for successful COD ability in tennis.

Eccentric Strength

Mark Kovacs of iTPA has written before about deceleration ability in tennis. We’ve already seen how deceleration ability plays a major role in helping protect the shoulder during high speed serves but we can also look at deceleration ability from a movement perspective. As you approach the oncoming ball, the braking forces to set-up for the shot can be quite high. Braking forces are linked to eccentric strength - and in the case of movement, lower body eccentric strength. Spiteri et al (2015) also found that faster athletes with greater eccentric strength were better able to decelerate more effectively and make a faster transition between braking and propulsion. In other words, the better able you are at absorbing high forces, the faster and more effective your braking/deceleration ability and the smoother your transition to begin the propulsion phase.

Isometric Strength

Lastly, we have isometric muscle contractions. In the case of COD, sport scientists call this the plant phase. In other words, there’s a transition between braking and propulsion where no movement is occurring but high forces are still being generated. Isometric strength allows athletes to maintain a low position when changing direction. This is important for 2 reasons. If you lack isometric strength, you won't be able to maintain your body in place (in essence, you'll be fighting against momentum - it pushing you one way, you wanting to go the other way). Second, staying low when changing direction facilitates a better muscle length-tension relationship. Muscles produce more force at specific lengths, if they are too long (legs fully extended) or too short (legs fully bent), force will be minimized. Keeping a relatively low stance will enable optimal force production, allowing for greater re-acceleration during the propulsive phase. Not to mention you have to hit a tennis ball! Having a more stable posture will maximize power output and hence the outcome of your shot. Overall, all 3 muscle contractions have their place when it comes to faster, more explosive and more efficient transitions between braking, planting and propelling.

Anthropometric Factors

For those of you who’ve never heard of the word ‘anthropometry’ before, we’ll keep it simple. It basically deals with a person’s physique/physical attributes. Examples include body weight, body mass, body fat %, limb lengths, girth measurements etc. Why would this be important? Well, as we’ve discussed previously, relative strength (i.e. strength to body mass ratio) has been linked to better acceleration and speed times in elite athletes. As reported by Spireti et al (2015), having a lower body mass AND a lower % body fat ratio, relative to strength, is also linked with faster COD test times. Essentially, lower body fat can have big impacts on your abilities to change direction rapidly & efficiently as there is less nonfunctional mass (nonfunctional in this case meaning, non-contractile).

Reactive & Stretch-Shortening Cycle Ability

A while back I wrote a post about lower-body plyometrics. We distinguished between fast and slow components of the SSC (stretch-shortening cycle). Here’s a quick recap. Both fast & slow components are seen during plyometric activities. In other words, when running and jumping (for example), we store and utilize elastic energy, thereby augmenting power output to levels higher than if disregarding elasticity altogether. The fast component refers to this elastic utilization when ground contact times are very short while the slow component deals with longer ground contact times. Both are relevant, at different times and both have a reactive component (it’s presence is much higher in fast SSC movements). When serving, the slow SSC is emphasized as you have a greater knee bend (amplitude), which will allow you more time to develop power. When split-stepping, you have less time so your ground contact time will be shorter - the shorter this time, the higher your impulse must be to effectively propel yourself towards the ball.

Plyometric activities that emphasize the fast component - like hurdle jumps, tuck jumps, depth & drop jumps - in multiple directions, are extremely effective in improving reactive strength, a key factor in improving COD ability. If this is the case why would we do slow component exercises - like broad jumps, vertical jumps, single-leg hops for distance etc? Because the slow component helps augment/potentiate the fast component. Ok, then why not just perform plyometric exercises to improve COD? Why strength train? Good questions. Unless you’re naturally very strong to begin with, improving strength capacity will also augment/potentiate all of these other qualities - reactive strength, explosive strength, power etc. And tennis is already VERY plyometric to begin with. That means that if you’re already spending multiple hours on the tennis court doing a variety of drills and point scenarios, you’re already training a lot of these elastic qualities. What you’re not doing however, is improving your muscular strength & neuromuscular capabilities - this has to be done with sufficient load in the weight room. Furthermore, to my knowledge, strength training is the best way to improve body composition (i.e. lower body fat %). Remember, only muscle contracts, fat doesn’t.

Final Comments

My objective in this post was to distinguish between agility and COD. While COD deals only with physical/technical qualities, agility encompasses both perceptual/decision making factors ALONG WITH COD factors. Furthermore, the aim here was on figuring out the mechanical requirements to change direction effectively, as these are more trainable outside the tennis court. That said, let's not beat around the bush, a well-rounded strength, power and plyometric program is essential in tennis. That means lifting heavy loads and performing explosive jumps & throws. It doesn't mean having "fast-feet" - from a mechanical perspective, this doesn't have any relevance to movement in tennis (or any sport for that matter). You need to be able to produce force and you need to be able to produce it quickly. That's what defines good change-of-direction ability in tennis. I hope, that's how you'll begin (or continue) to train.

WANT TO BE UP-TO-DATE ON THE LATEST SPORT SCIENCE AND TENNIS RESEARCH?

No spam or fluff - just the most comprehensive articles on tennis.