I’ve previously written about the split step and it’s importance to successful movement - and ultimately, shot execution - in tennis. But do we truly understand what factors contribute to an effective split step? Why we should devote serious attention to it? Or even more, how to best train it?

Before we get into the details, you should know that there are 3 primary components that make up the split step:

Timing

Technique

Physical Capacity

The split step, in my opinion, is arguably the most relevant movement quality a high level player must possess. If a player lacks this ability, they likely won’t be able to reach their full movement potential (no matter how explosive, strong or fast they are).

Let’s explore the underlying components and provide a practical progression on how to train the split-step effectively.

Split Step Timing

Several studies have explored the timing of the split step (Shim et al 2005, Uzu et al 2009, Filipcic et al 2017, among others). The consensus agreement from these papers is that split step timing is critical when it comes to being better prepared for the oncoming shot. Most researchers - including a colleague of mine, Cyril Genevois (PhD in Sport Science) - believe that better split step timing will likely decrease the number of errors a player commits.

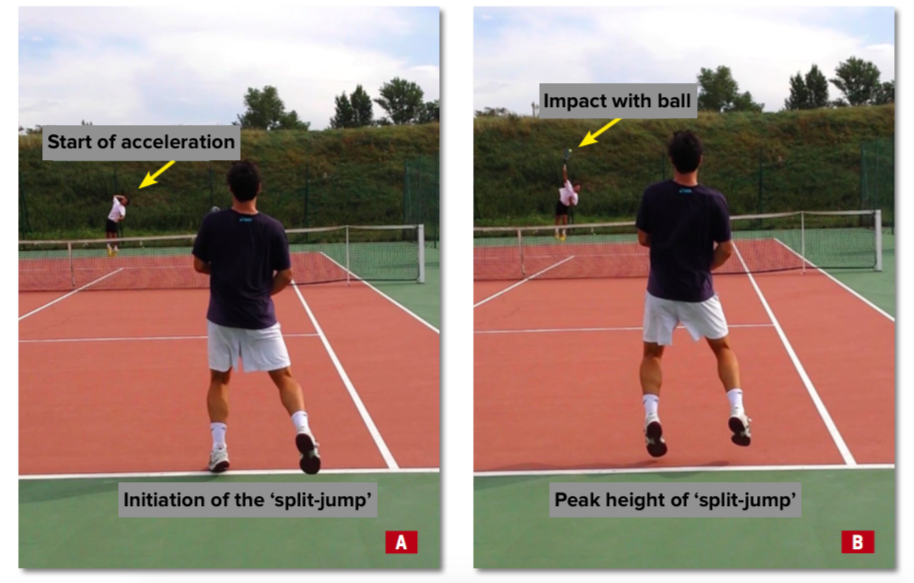

So when is the correct time to initiate the split step? Let’s use a serve and return example (figure 1 below) to outline the basic split step timing sequence (this represents the timing pattern for a high level player):

The server begins the acceleration phase/action. At the same time, the returner initiates their ‘split jump’ (the jump component of the split step).

The returner reaches the peak of their split jump at the moment when the server is making contact with the ball.

While airborne, the returner attempts to pick up various cues from the server (ex: ball toss, shoulder rotation, racquet face angle at impact etc).

As the returner begins his/her descent, just prior to hitting the ground, they know which direction they’ll initiate their movement and thus begin organizing themselves while still in the air.

Figure 1 - Courtesy of Genevois

Notice that the split jump DOES NOT begin when the opposing player is making contact with the ball and certainly NOT after they make contact with the ball. When players time their split late, they’re not only late on the ball, they generally look ‘slow’.

It’s amazing, however, how often I’ve heard coaches say “split at the very moment the player makes contact with the ball”. As a young coach, I echoed the same (I was merely following what other, more experienced coaches were cueing). But just look at the best in the world and you’ll see exactly their timing - and how early it truly is.

In this example, Federer initiates his split before Wawrinka even begins to accelerate the racquet (image to the left). His peak split jump height occurs just before Wawrinka makes contact with the ball (image on the right). At the top levels of the game, the pace of play is fast. Every tiny advantage a player can get, they take it (Federer does this a lot).

Have you ever seen a returner get aced and not even move a muscle? In my opinion, this happens too often and is caused by a momentary lack of focus. The player simply didn’t even initiate their split jump. All players should at least initiate a split step on every return of serve. Especially now that we know it happens before the server makes contact with the ball.

Ok, so before we move on, just how important is split-step timing? Shim et al (2005), found that volleyers who timed the split-step well, gained 25% more time compared to timing it late. The result was that they gained 60cm of reach while at the net. I don’t know about you, but in my opinion, that’s pretty substantial.

Split Step Technique

Technique and timing (and even physical abilities) are related. I wanted to present the timing first as it has large implications on how the remainder of a split step movement will be initiated and then executed.

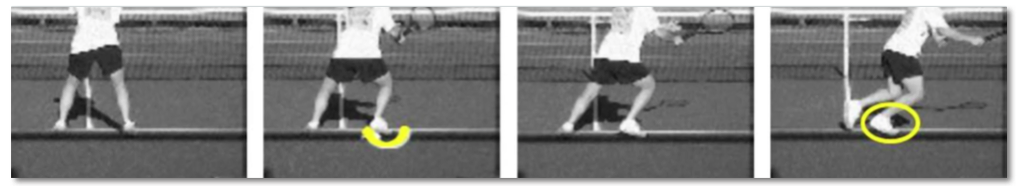

The old way to split

In the past, players were instructed to time the split when their opponents were making contact with the ball. We’ve outlined why this is incorrect. But beyond that, they’d tell players to land on both feet simultaneously and then initiate their first step towards the intended direction of movement (figure 2 below).

Figure 2 - Courtesy of Genevois

This was perhaps ok years ago when the pace of play was slower. But in today’s game, it’s no longer acceptable.

How you should be split stepping

There are different techniques depending on the situation a player finds themselves in, but in general - as was outlined above - high level players initiate their split step while their opponent is beginning their strike and are at their peak jump height before the opposing player makes contact with the ball. While on their way down, they already know which direction they’re going to initiate their movement. That means that when they first make contact with the ground, they usually do so with the opposite/exterior leg (figure 3 below).

Figure 3 - Courtesy of Genevois

Prior to hitting the ground, the interior/lead leg opens up toward the direction of the movement, and at the same time, the opposite/exterior leg begins an explosive action which ultimately initiates a lateral displacement (and the first step). This means that when the interior leg eventually does touch the ground, the foot is in-line with the centre of mass - this allows the player to be in a better position to accelerate.

Other key characteristics that define the split-step include: a greater lateral push with the outside leg on more difficult balls & those that are further from the player; the opposing/exterior leg begins showing muscle activation patterns before actually making contact with the ground; and the height of ‘split jumps’ vary depending on the player, their physical abilities and the situation at hand.

Special circumstances + variations

There are a few other split step variations that researchers (Genevois, Kovacs etc) have depicted and written about. For example, in short time and high pressure situations, some players adapt by landing with the lead/interior leg first. This is also the case when their previous recovery step came from the same direction they must move to on the current ball - i.e. the opponent is hitting behind them (figure 4 below).

Figure 4 - Courtesy of Genevois

Other players land with both legs simultaneously - but both are already positioned towards the direction of the movement. This allows the exterior leg to act as an anchor and the interior leg to position itself behind the centre of mass, enabling it to act as the driving leg.

What I’ve also noticed, under really extreme defensive positions, players aren’t really jumping but rather ‘dropping’ into a staggered stance and initiating the movement from there. Look at the images of Federer below - he’s saving time by getting down right away. In fact, this could save around 180msecs (which seems to be the average amount of time a player is in the air during a split). Again, in tennis today, time is precious.

Physical Capacity

If you’ve read some of my previous work on this topic, you know that reactive strength (or reactiveness) is a key determinant of split step ability. Reactiveness is a type of plyometric activity which relies heavily on the fast stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) action. On top of that, ankle and leg stiffness is a key underlying component of reactiveness.

Think of a spring - if it’s too compliant (or bouncy) there’s a lot of energy loss and therefore not a whole lot of rebound. If, on the other hand, the spring is too rigid/stiff, it doesn’t release it’s potential energy and again, no rebound. But somewhere in between, there's a spring that has just the right amount of stiffness/compliance - and thus, a high amount of rebound.

The same principle applies to the muscle-tendon complex of the ankle - and to a lesser extent - the leg. So when a player hits the ground after a split step, without a good balance between stiffness and compliance at the ankle, the potential energy will be lost - in other words, there’ll be too much force absorbed by the ground.

Think ‘react’ while in the air

Like we mentioned earlier, the support/exterior leg has greater gastrocnemius (calf) muscle activation patterns compared to the lead/interior leg on the descent from a split jump. What this tells us, is that elite players, while in the air, are already thinking about moving explosively even before they can initiate the movement.

Practically, when training to enhance the physical capacities of the split step (and subsequent first/initializing step) we must instruct players to have the same idea; i.e…“before landing, already begin thinking of reacting explosively” or “prior to landing, think of applying force very quickly into the ground”.

Whether we’re targeting more general stiffness/reactiveness qualities through depth jumps, specific movements via split step drills or even during actual tennis exchanges - to get better, we must not only time the split jump well, but we must also think about using the ground effectively to get off to a quick start.

A 3-Drill Progression

Below are 3 drills that could act as a simple progression - from more general to more specific - targeting the split step in a closed to open environment.

Exercise 1 - Lateral Depth Jumps

Exercise 2 - Split & Go Diag Fwd

Exercise 3 - 4-Cone Agility Drill

Finally, when taking this to the court, there is a heightened awareness of what it takes to execute a high level split step. But the focus can’t subside there. The player has to still do the following: a) perform their split at the right time and b) figure out the direction they need to move while in the air and c) think about being highly reactive when they do finally make contact with the ground.

What I’ve seen is that when an elite player adheres to the 3 points I just mentioned, they organize their body - and foot/leg placements - in the most ideal positions to execute the desired movement efficiently and under the shortest possible times.

That doesn’t mean that technique isn’t important. It is. It just means that other factors - perception, timing, physical capacities - are often limiting a player’s movement abilities.

WANT TO BE UP-TO-DATE ON THE LATEST SPORT SCIENCE AND TENNIS RESEARCH?

No spam or fluff - just the most comprehensive articles on tennis.